Reframing the Present: Yuhanxiao (Maggie) Ma on Systems, Fiction, and Truth

Yuhanxiao (Maggie) Ma is a research-based artist and creative technologist whose work unpacks the systems that quietly govern our everyday lives. Using various forms of design as a language (objects, installations, and digital tools), she communicates her observations of knowledge systems and interrogates the assumptions society often holds about scientific progress and innovation. Projects like Modest Witnesses and A Clock in Progress reveal how these systems shape not only what we consider “truth” or “progress,” but also how we see the world and our place within it. Through carefully constructed environments and speculative interventions, Ma invites us to slow down, reflect, and reconsider the structures we move through, often without noticing.

In this interview, we explore her approach to form and fiction, her process of reframing the present, and how audience responses continue to shape the evolution of her work.

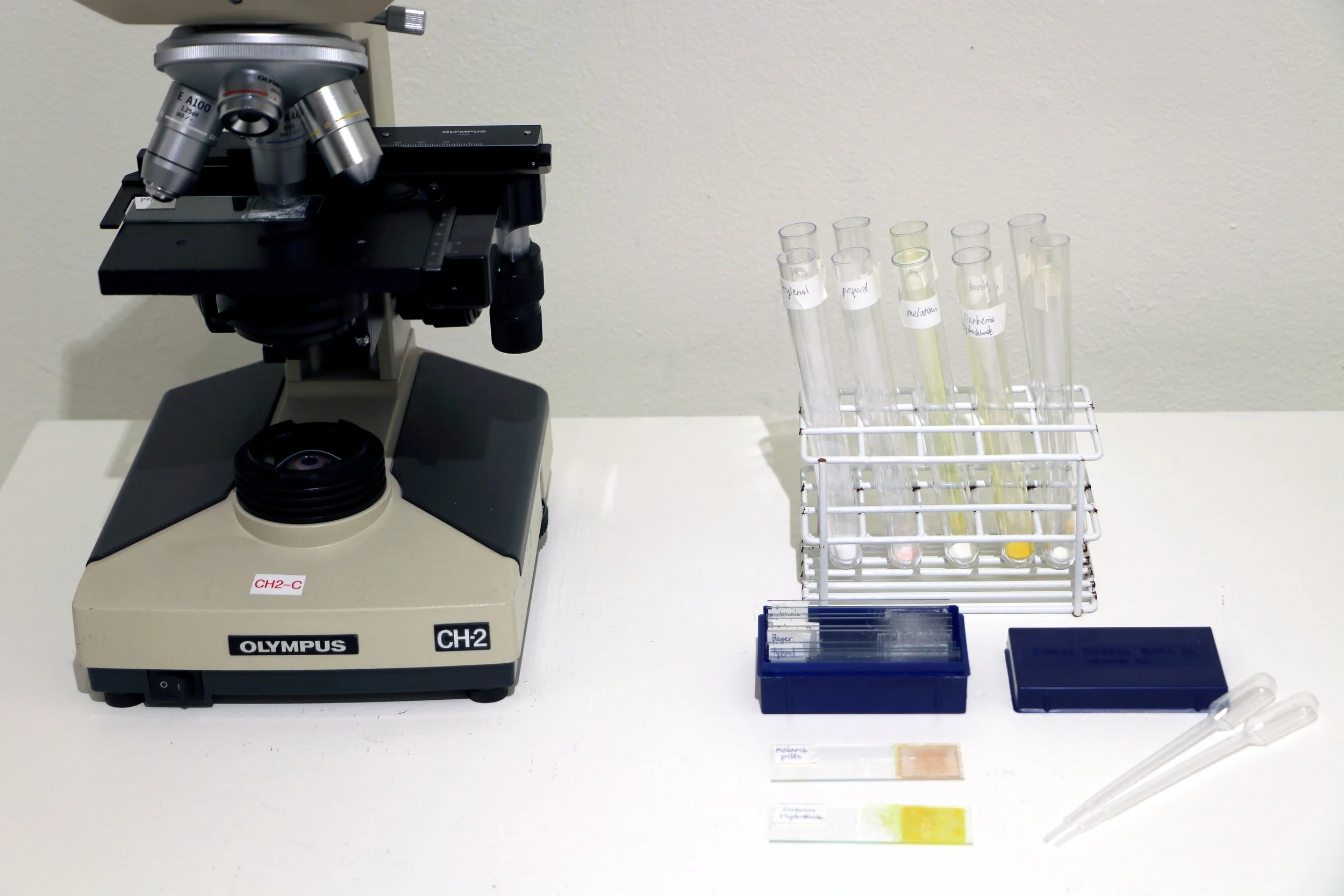

“Modest Witnesses,” 2024. Part of the Group Exhibit Metabolically Yours, SVA Bio Art Summer Residency.

Your work often subverts systems we take for granted (like pharmaceutical innovation or timekeeping) through sculptural and speculative design. What drew you to explore these themes, and what role do storytelling and design fiction play in bringing these ideas to life?

I’m drawn to these systems because of how deeply they structure everyday life while remaining largely unquestioned. Pharmaceutical logic, for example, often operates as an unquestioned proxy for progress, and timekeeping feels like pure infrastructure—but human decisions, political forces, and cultural assumptions shape both. I'm interested in gently prying those open.

Storytelling and design fiction allow me to shift perspective without being didactic. I use fiction not to predict the future but to reframe the present—often through objects or systems that appear plausible, yet contain intentional inconsistencies. In Modest Witnesses, for instance, I treat pills as archival witnesses to human ambition and institutional authority. The fictional elements aren’t meant to deceive but to invite reflection: What do we accept as truth, and who gets to decide?

The idea of reframing the present really comes through in your work, especially in how you create space for reflection without prescribing what one should think. You invite us to question what we might take for granted in everyday life (like pharmaceuticals, which are often seen as essential to a healthy society, yet carry controversial complexities).

How do you go about reimagining or, as you say, reframing the present in your installations? In other words, how do you define or measure truth through your creative process?

For me, reframing the present begins with looking for the points where everyday systems reveal their seams — the overlooked details, contradictions, or inefficiencies that hint at the human decisions behind them. I’m not interested in delivering a single “truth” to the viewer; instead, I create conditions where the audience encounters familiar systems made strange, so they must navigate their own interpretations.

In my installations, I often construct environments that feel authoritative and plausible, an archive, a testing center, a pharmaceutical display. Within them, I embed subtle inconsistencies: mislabeled objects, contradictory timelines, or speculative species that blur the boundary between human and nonhuman. These frictions are designed to slow the viewer down, to make them question not just the installation’s logic, but the broader systems it mirrors.

I think of “truth” less as a fixed endpoint and more as a negotiated space, one that is constantly shaped by power, access to information, and the stories we choose to privilege. My process involves gathering factual research, but also deliberately inserting fictional or speculative elements. The interplay between the two becomes a way to measure truth: not by whether something is factually correct, but by how it influences perception, belief, and critical engagement.

Ultimately, I see my role as creating a framework for inquiry rather than delivering fixed answers, inviting viewers to confront and weigh multiple, even conflicting, truths. In my work, truth is measured by its ability to unsettle assumptions and compel a closer, more critical examination of what once felt certain.

“Being lied to is never a good feeling. Yet in an artwork, that moment of realising you have been misled can be surprising and even productive. It creates emotional engagement and critical distance at the same time.”

If what people perceive as truth influences their beliefs, how do you approach shaping that perception in your practice? Are you intentionally aware of what you choose to reveal, distort, or leave open to interpretation?

I often work with the seemingly objective representations of science, such as reports, questionnaires, and medical forms, because they carry authority in everyday life. What interests me is how quickly that sense of authority unravels when you look closer. My goal is not to provide fixed answers but to pose questions that invite critical thinking about the systems we engage with every day.

I was deeply influenced by the art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s writing on parafiction and by artists like Inmi Lee, who both explore the unstable border between truth and fiction. Being lied to is never a good feeling. Yet in an artwork, that moment of realising you have been misled can be surprising and even productive. It creates emotional engagement and critical distance at the same time.

What types of reactions do you hope to elicit from your audience? Could you share an anecdote from a project that sparked a response you either anticipated or that was new and surprising to you? Has an audience’s reaction ever changed your own understanding of truth or shifted your perspective?

In The Guinea Pig Eligibility Test, I designed a questionnaire modelled on clinical trial forms. In real life, people sometimes lie on these forms by hiding pre-existing conditions or exaggerating symptoms in order to become eligible and get paid. In my work, I reversed that logic. People with privilege had to lie in the opposite direction, claiming disadvantage in order to qualify for the “reward” of becoming a guinea pig.

One audience member later shared with me that she lied the first time she filled out the form because she always lies on medical questionnaires. She has anxiety but never marks “yes” when asked about preexisting health conditions, because she worries it might limit her opportunities in the job market. So in the first round, where participants are supposed to tell the truth, she lied out of habit. But in the second round, where participants were supposed to lie about privilege, she actually answered truthfully.

That reaction stayed with me. It showed me how deeply ingrained these habits of self-protection are, and how the work could surface them in unexpected ways. It shifted my own understanding of the piece, reinforcing that truth in my practice doesn’t sit only in what I construct. It also emerges through the audience’s negotiations with their own experiences of vulnerability and power.

“The Guinea Pigs,” 2024. Multimedia Installation. Selective laser sintering 3d printed sculptures and a selection of pills; lightbox, backlit film prints.

That story says a lot about how your work creates space for personal reflection, not just on the systems themselves, but on how people relate to and navigate through them. Could you share more about how you decide on the format or interactive medium for each piece? How do science or technology come into play in your research, process, or the final output?

The formats and media I use usually come from the systems I want to investigate. Questionnaires, medical reports, x-rays, and microscopic images all carry the aura of science, and I reframe them to expose the logics they conceal. My process is closer to problem-solving in science: I start with the issue I want to investigate, then choose the medium or technology that will make it both visually striking and conceptually sharp. For The Guinea Pig Eligibility Test, I needed custom software, facial recognition, and animation, which I developed in collaboration with the animation artist Anna Ren. In A Clock in Progress, I rewired clocks and used Arduino to probe how time is standardised and represented. In An Almost Exhaustive List of Pills, I used audio because repetition and accumulation were the most effective ways to expose the overwhelming presence of pharmaceuticals in our lives.

Do you ever adapt your work based on how people interact and respond to it? I’m curious how audience reactions feed back into your research or shape what you make next.

Yes, I often adapt my work based on how people interact with it. I think of exhibitions less as static presentations and more as experiments that unfold in public. Audience responses are not just reactions; they are intersubjective exchanges that become part of my research archive. Some visitors respond playfully, others with unease, and those emotional registers matter because they reveal where trust, doubt, and vulnerability collide.

For The Guinea Pig Eligibility Test, I had assumed that most visitors would be too privileged to become guinea pigs on their first try. But a few participants transformed without needing to lie. That outcome pushed me to think about adjusting the parameters in determining who can be eligible. In the U.S. context, privilege can act as a shield, but globally, bodies are often made eligible for testing much more easily and with far fewer safeguards. Encounters like this remind me that the “truths” in my work emerge through the intersubjective negotiations people bring with them.

Lastly, where do you see the intersection of art, science ans technology heading in the future? Are there any emerging trends or technologies you’re excited to explore? How do you see your work evolving in the near future?

Increasingly, I see artists treating technologies as cultural artifacts—objects that reveal how societies imagine progress, negotiate authority, and make meaning. I think the future of art, science, and technology lies not in keeping them apart, but in understanding them as intertwined systems that both reflect and shape culture. What excites me is not only how a single culture interprets a system, whether it’s time, medicine, or data, but how those interpretations shift across cultures, carrying different assumptions, values, and contradictions.

For me, parafiction is one way to engage with this complexity. It makes space to inhabit multiple truths at once, to acknowledge how fragile and contingent our systems really are, and to imagine what else they might become. I see my own work evolving in this direction: building speculative frameworks that don’t prescribe futures but instead create openings to question what feels self-evident in the present.

Welcome to The Art in STEAM podcast

Expect to spark ideas through personal stories told by women in STEAM, from robotics to technology, digital media and the climate crisis.